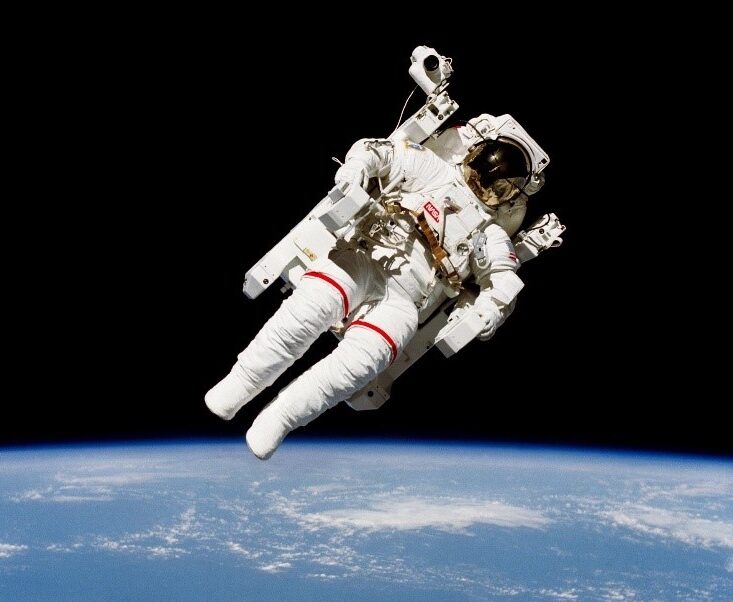

Bruce McCandless II during the first untethered EVA (1984). Credit: NASA.

Part 1: Orbital EVAs

Dr. Laura Thomas, Science Communicator for JSAR / The Mars Society

10 min read

Some of the most iconic images in human spaceflight have been captured during EVA (Extra-Vehicular Activity), from Buzz Aldrin standing on the lunar surface and Bruce McCandless II drifting freely above Earth. Spacewalks capture the imagination for good reason. They represent the boldest edge of human exploration. But they’re also among the most dangerous, technically complex, and tightly controlled of operations.

An EVA refers to any task performed outside the spacecraft and its life-support ecosystem. Once an astronaut steps outside the hatch, they are directly exposed to the vacuum of space. That fact makes EVAs one of the highest-risk phases of any mission, which is why they are planned down to the minute and rehearsed extensively on Earth before anyone ever leaves the airlock.

Spacewalks are not just a test of mechanical skill either; they stretch the body and the mind. Astronauts must perform precise manoeuvres with limited sensory feedback and high cognitive load, often for hours at a time, all while wearing a pressurised suit that alters natural movement and perception. Fine motor control, spatial awareness, and emotional management must be trained under these conditions. Success depends as much on psychological readiness and team coordination as it does on engineering competence.

Part 1 of this blog focuses on orbital EVAs, commonly known as spacewalks.

What kinds of tasks are completed during a spacewalk?

Most spacewalks revolve around engineering: maintaining structures, repairing systems, assembling new modules, or upgrading existing ones. The International Space Station (ISS), now in its 26th year of human occupancy, requires regular exterior servicing. Significant wear and tear is caused by continual exposure to radiation, orbital debris, and extreme temperature cycling as the station moves in and out of sunlight roughly every 90 minutes.

Other types of spacewalks support scientific experiments, inspections, or technology demonstrations, but these are less common. The famous photograph of Bruce McCandless II, for example, shows him testing a nitrogen-propelled jetpack called the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), designed for full untethered mobility. Astronauts today remain tethered as a primary safety measure, but the ability to self-rescue remains a core safety capability.

EVA Preparation and Life Support

Spacewalk preparation begins long before exiting the hatch. The day before, astronauts shift to a low nitrogen diet, reduce strenuous activity, and start breathing pure oxygen to flush nitrogen from the bloodstream. On EVA day, astronauts don (put on) their spacesuits and enter the airlock for pre-breathing and depressurisation. Much like in scuba diving, these steps prevent decompression sickness and help astronauts transition to the lower-pressure environment inside their suits. A spacewalk officially ends once the crew returns to the airlock, repressurizes, and has safely doffed (removed) their suits.

Intra-vehicular crew (Thomas Reiter) assisting astronaut Jeff Williams suited for EVA inside the Quest Airlock. Credit: NASA.

NASA astronauts use EMUs (Extravehicular Mobility Units), Roscosmos cosmonauts use Orlan suits, and China’s CMSA taikonauts use Feitian suits. Despite their differences, all spacesuits function as pressurised portable life-support systems (PLSS). For the astronaut inside, the suit becomes both their environment and their protective shell against the vacuum of space, radiation, and micrometeoroids. Breathing, temperature regulation, and movement are no longer automatic or intuitive. Wearing the suit alters how exertion is experienced and means that fatigue can build quickly over the course of a spacewalk.

All major spacefaring nations conduct EVAs. China conducts regular spacewalks from the Tiangong station, and in 2024 SpaceX’s Polaris Dawn mission completed the first commercial EVA, marking a significant milestone for private-sector human spaceflight.

Fun Fact: Cosmonaut Anatoly Solovyev holds the male record for most cumulative spacewalk time, with over 82 hours. Astronaut Sunita Williams currently holds the female record with over 62 hours.

How do astronauts train for spacewalks?

Classroom Training

EVA training begins on the ground. Before touching water or wearing a suit, astronauts first learn procedures, timelines, and contingency responses by building familiarity with tools, hardware, and decision logic. This foundation is essential, particularly when later operating under stress or time pressure.

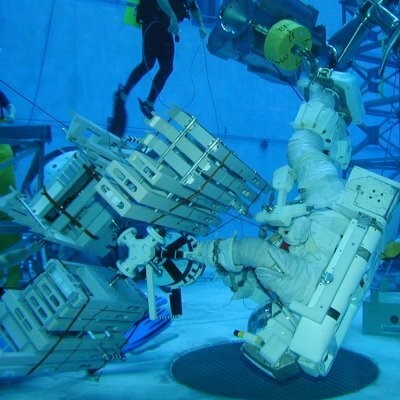

Neutral Buoyancy Training

Much of spacewalk training takes place in Neutral Buoyancy Labs (NBLs) such as NASA’s facility in Houston, the Gagarin centre in Russia, or ESA’s pool in Cologne. Neutral buoyancy means staying suspended rather than floating upwards or sinking. This state allows astronauts to focus on task execution without constantly compensating for body position. It’s the closest sustained approximation to weightlessness on Earth, even if water drag prevents it from being a perfect microgravity analog.

These enormous pools contain full-scale ISS module mock-ups where astronauts rehearse manoeuvres, body positioning, and hardware operations. As a rule of thumb, every hour of spacewalk time equates to around 5 to 7 hours submerged in the NBL. Scuba divers support astronauts during these rehearsals by adjusting buoyancy, managing suit positions, and assisting with tools as required.

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at Johnson Space Center. Credit: ESA – S. Corvaja

Neutral buoyancy training reinforces tether discipline, body alignment, and efficiency of movement, all essential for stamina and safety. Standard training includes ingress and egress (entering and exiting) both EMUs and the airlock, tether swaps, handrail navigation, and using tools without slippage. Once in space, tools are attached to the astronaut’s EMU so that they do not drift away the moment they let go.

With enough repetition, technical and complex tasks shift from conscious effort to procedural memory. This transition is not just a performance advantage; it serves as a safety feature. If something goes wrong or when fatigue clouds judgement, competence has already become automated.

Robotics Training

Increasingly, modern spacewalks rely on robotics, particularly the Canadarm2. Pressurised gloves dramatically reduce dexterity, so astronauts train extensively in mixed-reality simulations and underwater rehearsals. Practice helps with mastering grip control, precision placement, and coordinated handoffs between crew and robotic systems. Familiarity also builds shared situational awareness. Over time, this human-machine teaming develops through a process known as trust calibration, which is learning when to rely on machine precision and when human experience should take the lead.

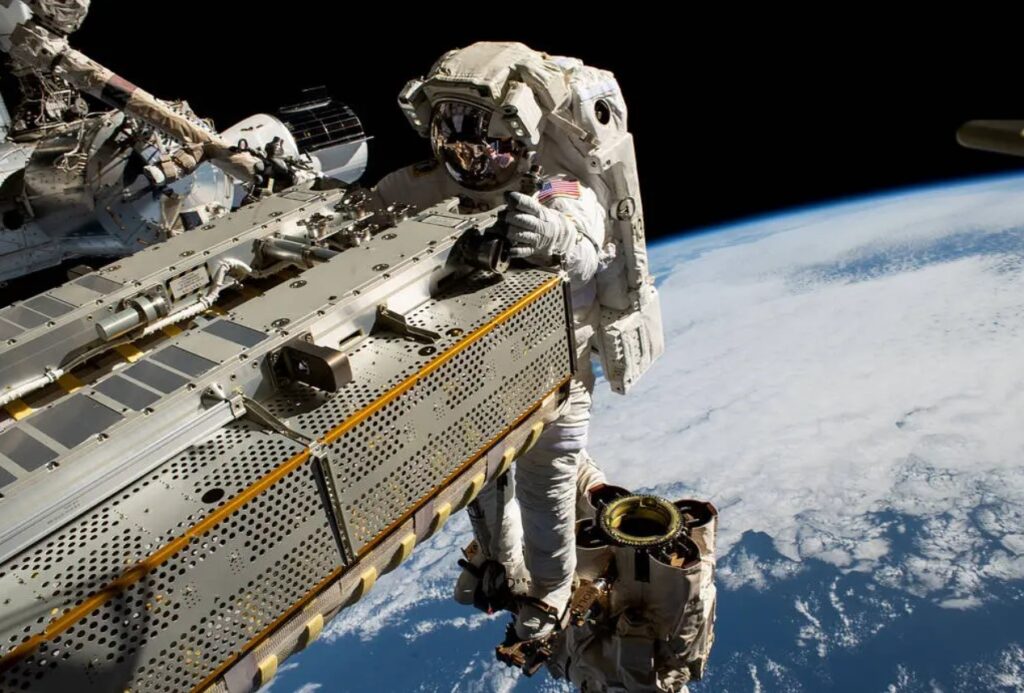

Astronaut Woody Hoburg riding the Canadarm2 robotic arm. Credit: NASA

Countermeasures for Spacewalks

Spacewalks are long (typically 5-8 hours), physically taxing, and cognitively intense, placing sustained demand on attention, decision-making, and posture. EMUs can be rigid and heavy, causing strain on the neck, shoulders, and back after long periods of wear. Training therefore emphasizes endurance, movement efficiency, and emergency response, rehearsed in both virtual reality and neutral buoyancy environments.

Astronaut Christer Fuglesang practicing for a spacewalk in the NBL. Credit: NASA

Emergency procedures are drilled repeatedly. Astronauts rehearse responses to visor fogging, CO₂ spikes, communication failures, equipment malfunctions, and water intrusion. The near-drowning of ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano in 2013 caused by a clogged filter remains a defining example of how rapidly circumstances can escalate, and how critical training and crew coordination are for survival. His safe return depended on his composure, spatial memory, tactile navigation back to the airlock, and the fast response of the IV (intra-vehicular) crew.

Recurring helmet water-intrusion events prompted NASA to temporarily pause EVAs in 2022–2023. That pause accelerated the development push for next-generation suits such as NASA’s xEMU and Axiom’s AxEMU. Both suits are designed to support Artemis lunar missions with improved mobility, cooling, and dust protection (more on these in Part 2).

Fun Fact: One of the lesser-known hazards of spacewalks is hand fatigue from working in pressurised gloves for long periods. Sustained grip force can lead to fingernail delamination, which is why astronauts’ hands and fingernails must be checked before every spacewalk.

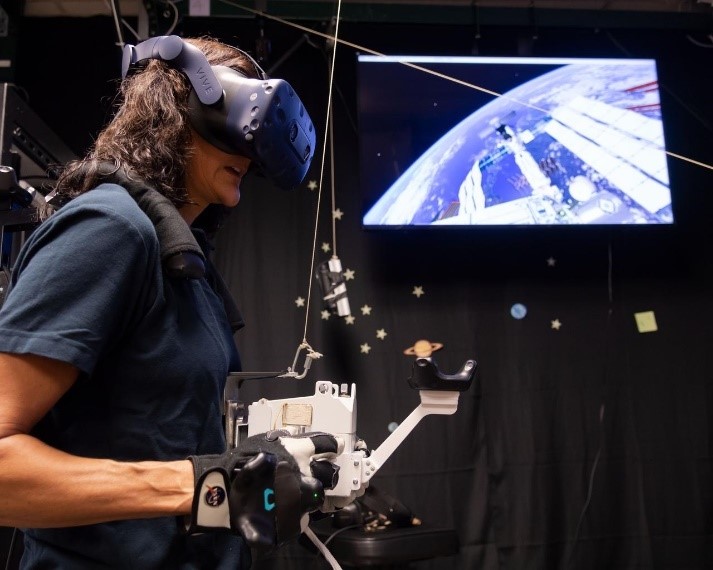

Untethering Training

Untethering, which means accidentally drifting away from the station, is highly unlikely, but remains one of the most disorienting emergencies imaginable. Astronauts practice recovery in NASA’s Virtual Reality Lab using a virtual replica of the jet-powered self-rescue SAFER (Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue) backpack to simulate manoeuvres.

These sessions teach astronauts how to stabilise uncontrolled rotation, acquire sight of the station, and use controlled fuel-efficient bursts to navigate quickly back to safety. Crews implement precautionary measures to prevent this scenario entirely, such as using multiple tethers, anchor points, and strict procedural checks.

Astronaut Suni Williams practices spacewalking at NASA’s VR Lab. Credit: NASA

Fun Fact: While it may take creative liberties with orbital mechanics and space debris, the movie ‘Gravity’ conveys the disorientation and intensity of an uncontrolled drift. In fact, several astronauts have praised the movie for its realistic depiction of EVA engineering operations. Definitely worth a watch!

Human Factors & Saturation Training

EVAs are never solo endeavours and success depends on working as a team. Spacewalks rely on tight coordination between:

- EVA crew outside the station

- IV crew inside the station

- Mission control teams on Earth

Clear communication, teamwork, and emotional regulation are as critical as technical skills. To prepare, astronauts train for spacewalks under saturation conditions, scenarios in which cognitive load, sensory input, and task demands exceed typical capacity. These conditions create the moments when errors are most likely to occur, as attention narrows, working memory overloads, and small issues start to accumulate. This training helps to develop calm and precise execution even while under sustained pressure.

Historically, this training has taken place at NEEMO (NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations), based at the Aquarius Reef Base in Florida. Underwater missions at the base simulate EVA-style stressors such as restricted mobility, communication challenges, task overload, physiological discomfort, and uncertainty.

NEEMO crew outside Aquarius Reef Base, used for EVA analog missions. Credit: NASA/Karl Shreeves

Takeaways

Spacewalks are among the most exhilarating yet hazardous tasks in human spaceflight. They blend precision engineering with human adaptability. Every movement is choreographed and every contingency is rehearsed. This depth of preparation is what enables astronauts to work safely and precisely while operating in a hazardous environment.

So the next time you assemble IKEA furniture, spare a thought for the astronauts doing similar tasks, only in a pressurised suit and gloves, 400km above Earth travelling at 28,000km/h, with no floor to hold anything still!

Orbital EVAs are just the beginning. Surface EVAs introduce new challenges: gravity, dust, terrain, and radically different suit designs. Part 2 will explore how astronauts operate on the Moon, Mars, and in analog environments.